How shifting from communal tales to individual heroes reshaped our sense of magic, selfhood and what a story is even for.

Last time, I asked why we treat our storytelling paradigms as if they’re hardwired into the human brain.

I mean, we westerners.

The paradigm we’ve come to know as Story – linear, heroic, growth fuelled through conflict – has become a dominant force, thanks mostly to the cultural imperialism of Hollywood, I guess.

But I argued that wasn’t the only shape in town. Far from it. Other cultures tell stories differently – sometimes wildly differently – and yet we act as if Aristotle nailed it thousands of years ago in the same way that Einstein found an essential and eternal truth of gravity.

That little exploration left me with another question: how did the Western canon end up like this in the first place?

What’s the origin story of Story?

If our stories look so unlike the mythic, cyclical, communal forms found elsewhere, what happened to us along the way?

Why did we split from our myth-laden roots? And – chicken-and-egg – did our storytelling evolve because our culture changed, or did our culture change because our stories trained us to think in certain ways?

Have we somewhere in the middle of all that progress and pragmatism, misplaced a deeper idea of magic?

Time for another root around among the scholars.

1. When stories belonged to everyone — and to the world itself

Early European tales, like those across most of the world, were communal and cosmological. They reinforced the universe rather than resolving a character’s personal crisis. Time was cyclical; magic wasn’t an exception but a condition of reality, a byproduct of awe. Nothing hinged on an individual’s choices because the individual wasn’t the single unit of meaning.

2. The emergence of the inner life

Over centuries, Europe became increasingly fascinated by the self. Christianity centred the soul as a moral project, moving from dark to light. Gradually the action moved inward. Stories began to orbit individual decisions, inner conflict, and moral responsibility.

3. Linear time and the promise of progress

Once history was imagined as a straight line rather than a cycle, storytelling followed suit. The plot became a journey with a point. Growth, development, revelation – these became the hallmarks of a “proper” story. Narrative progress mirrored social progress.

4. The birth of the modern self (and the modern novel)

By the 18th century, the individual was the star of the show. Robinson Crusoe, Jane Eyre, Pip, Elizabeth Bennet – all private people navigating private dilemmas. This wasn’t just art; it was a reflection of a society organised around property, literacy, aspiration, and personal mobility. Again, the loop tightens: the more we valued individualism, the more stories reinforced it. We gave ourselves a licence to be self-absorbed.

5. What got lost: the older idea of magic

In the shift towards interiority and realism, something disappeared. The West didn’t lose magic — we simply domesticated it, bent it to our narrative will. Think of Harry Potter: the ultimate story of magic, yes, but still anchored to character development, destiny, and the tidy machinery of a plot that must progress. Magic becomes style, window-dressing. It becomes genre.

What vanished was the older, mythic sense of magic as a condition rather than a tool: the porousness of reality, the communal imagination, the cosmos that breathed with the story.

How to use this knowledge

So what can writers actually do with all this? Should we break away from the Western norms to be extraordinary, or stay within them to be understood? The truth is less prescriptive and far more liberating.

The answer is extraordinarily simple: write the story.

That’s your job: write the story – deploy some truth, find some bigger truth.

- Why stories are the glue that holds us together

- 5 simple tips to unlock your story’s true potential

- How to find a compelling voice: stunning advice from a master story-teller

The form is an act of creation but the purpose is a byproduct. It will reveal itself. Whatever emerges on the page is usually what you wanted to do, whether you knew it or not. Narrative purpose often arrives long after the narrative itself.

We understand our stories in the rear-view mirror and shouldn’t ever start with a manifesto because that might stand in the way of occasionally ugly truths.

In the end, story is story. Its purpose is seldom visible at the start. You discover it only by writing — and then, if you like, by stepping back and noticing what ancient shape your words have traced.

Three turning points in Western storytelling

Hamlet (Shakespeare, c.1600)

A turning point in Western storytelling. The world is still threaded with myth, ghosts and fate, but the true drama has moved inside one person’s mind. Hamlet’s hesitation, doubt and self-analysis show the shift from communal meaning to psychological interiority.

Robinson Crusoe (Daniel Defoe, 1719)

The birth of the modern individual. Crusoe isn’t guided by gods or destiny; he builds a world by sheer will, labour and rational planning. It is individualism laid bare – resourceful, pragmatic and alone.

Mrs Dalloway (Virginia Woolf, 1925)

A modern portrait of the self in all its beauty and unease. The plot is simple, but the inner lives are vast. Woolf captures the glory and terror of consciousness: the private storms, the fragile identities, the relentless presence of memory and perception. Here the individual is no longer heroic or isolated – just very frail and human.

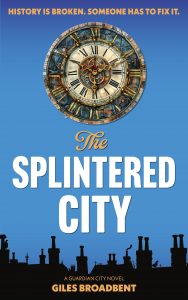

The Splintered City by Giles Broadbent is out now.