The page count in best selling books is getting smaller. People have no time any more. Are shorter books the next chapter in the publishing game?

Kiwi Rose Matafeo is a cracking comedian. Her recent West End show, caught on camera for the BBC, is full of zippy observations from a young woman trying, and failing, to live her best life in a frazzled modern world.

One observation caught my attention. Perhaps predictably.

She started on a riff like this, “I read this book that changed my life in a huge way.”

Later on, she interrupts herself to clarify that earlier point, “Obviously, when I say I read a book what I actually mean is that I listened to a podcast – because I am 27 years old and I haven’t read a book in four years. Books suck!”

Wait, what?

Is that it now for books, I wondered. Maybe the old crusty tomes are living out the last of their golden years as audiobooks (because they seem to be doing OK).

Are books past their prime?

But do books really suck now?

When the internet came along giving us a ton of streaming services to busy our minds, but then again so arose platforms such as Kindle Direct Publishing.

KDP and their allied services disrupted the entire publishing market. They allowed authors to find their audiences through niche markets across the globe. They made books accessible. They delivered mind-blowing technologies for the side-hustle author, such as cheap and quick print on demand.

The smartphone came along but it also gave us the Kindle, Kobo, Apple Books apps, making sure our ubiquitous friend can deliver up literature as well as memes, tweets and Instas.

People are reading, people are writing.

Books are doing OK, sort of. But should there be a more textured, market-led, less sentimental response to the cry of “books suck!” than – “we’ve seen it all before”.

With shorter books, less is more

Here’s one response.

Shorter books.

Why don’t we write shorter books?

If books as objects evolve to rise to the challenge of new technology, shouldn’t writers adapt and evolve as well?

So, again, I ask, why don’t we write shorter books?

There is an answer in mainstream publishing terms. The traditional publishing houses don’t particularly like shorter books. Maybe they’re hard to sell. Greater cost per unit, fewer words for your buck. Certainly, they don’t showcase the full lavish prowess of star authors or debutants.

The traditional publishing houses actively discourage the shorter novel and positively disdain the concept of the novella, the novella being a short story with pretensions.

- Book sales – er, there’s some good news and some bad news

- How to boost your SEO (without knowing a thing)

No, traditionally the hefty novel has been the way to go. The thunk of tome on table is the sound of cultural significance.

I’m asking, why? With all the technical facilities to produce and sell novels for pennies these days, why should the cultural hegemony of the publishing houses still dominate?

I can feel the chant growing – short-er books, short-er books.

The cry is coming from the consumers who are voting with their wallets.

Best sellers are shrinking

Here’s the evidence. This next revealing section comes from El Pais from May, 2022, and is based on a report from Wordsrated, an American non-profit organisation dedicated to discovering data about the world of books.

“What Wordsrated discovered is the unbelievable case of the shrinking best-seller. In the last decade (from 2011 to 2021) the average length of best-selling books in the United States, according to The New York Times lists has fallen 51.5 pages on average (from 437.5 to 386), which represents a decline of 11.8%.

“The probability that a book of more than 400 pages will enter the best-seller list fell by 29.5% in those years.”

Dimitrije Curcic, director of research for Wordsrated, pointed to the usual suspect – the grand theft of precious time – and he went on to make a telling point.

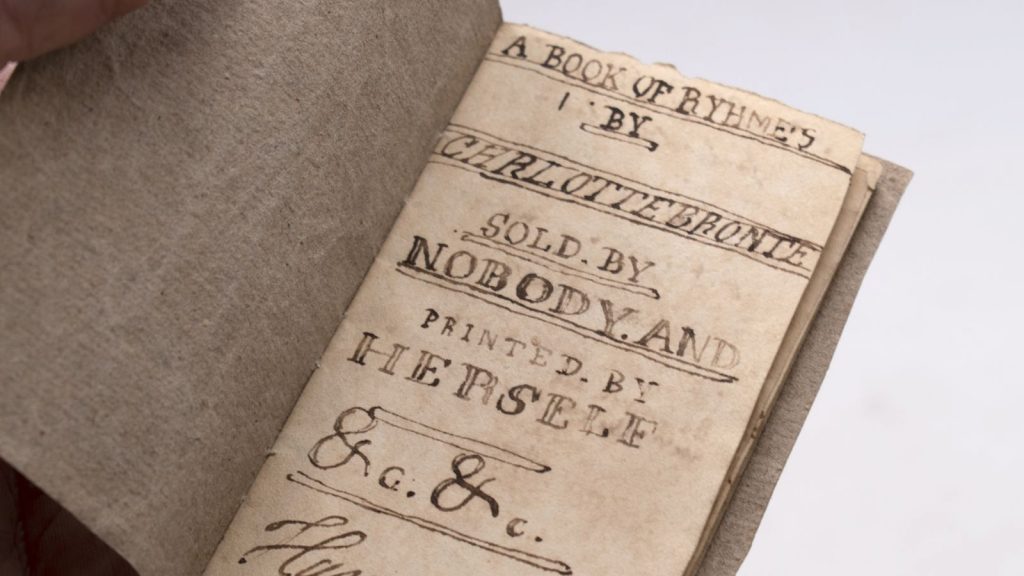

Not a shorter book, but a smaller one, from Charlotte Bronte

“I think average readers are less likely to commit to a longer book, rather, they choose something they consider more interesting and that’s realistic to complete.”

Realistic to complete. I love that. My Kindle is strewn with the half-mangled corpses of books I never got round to finishing. These include books I actually liked at the time, but after a period of neglect and distraction, they lost their sheen (just as I lost the thread of the plot.)

In fact, I’m currently on a campaign to finish half-finished books.

The El Pais article pointed out that people liked to sample more books from more authors – a literary tapas bar, a mixed tape of fabulists – while that old Sunday School sense of moral condemnation over an abandoned book no longer holds much currency.

This all contributed towards the rise of the slimmer volume.

How short is short?

So what is a shorter book exactly and how does it compare? Here’s a list of traditional sizes.

- Novels: 70,000-110,000 words

- Mainstream Romance: 70,000–100,000 words

- Sub-genre Romance: 40,000–100,000 words

- Science Fiction / Fantasy: 90,000–120,000 (and sometimes 150,000) words

- Historical fiction: 80,000–100,000

- Thrillers, mysteries and crime: 70,000–90,000 words

The sweet spot, authors are advised, is around 80,000 words. That means you’re a serious writer with purposeful intent. And, yes, that feels like a healthy heft, enough scope for you to build your world, develop your characters and wrap up your complex story at a steady pace.

Novellas are 30,000 to 50,000 words and tend to equate to one-act plays.

But what about the works of 50,000-60,000 words?

That gratifying feeling of finishing a book? Imagine that more often. The rat-a-tat-tat of slamming book covers, toppling like dominoes.

Doesn’t that feel do-able? And swift? And rewarding? Forcing the writer to be more disciplined, more judicious in their choice of paragraph, allusion, subplot and adjective.

This all reminds me of that famous quote (attributed to just about everyone), “I’m sorry this letter is so long, I didn’t have time to make it shorter.”

Think how that might change how you attack your story. Would you remove words, subplots, get to the point quicker, move with greater dynamism between key turning points? In doing that, wouldn’t you, the writer, be taking a view of story more like a film-maker, or a TV showrunner?

And isn’t that rhythm – that snappy timpani of frequent drama – isn’t that now the natural rhythm of the culture? Have we all just speeded up the metronome of cultural absorption?

Can I make a short novel work?

If you worry you won’t be able to pack a good story into a shorter form, here’s some famous writers who provided way more story with less ink.

- Lord of the Flies, William Golding, 59,900

- War of the Worlds, HG Wells, 59,796

- Slaughterhouse Five, Kurt Vonnegut, 49,459

- Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury, 46,118

- Double Indemnity, James M Cain 30,072

- Animal Farm, George Orwell, 29,966

- The Old Man and the Sea, Ernest Hemingway, 26,601

Yes, fantasy and sci-fi lends itself to the immersive six-figure lengths, allowing time for the author to tell a story and explain the lore, government, tribes and technologies of the world they have created.

These stories will always find an audience because that’s exactly what the audience wants – unsparing examination of distant cultures.

A Game of Thrones George RR Martin runs at 298,000 and the Lord of the Ring series 576,459.

And the classics (from the pre-Netflix days) will always be read:

- Bleak House, 360,947

- David Copperfield, 358,000

- Anna Karenina, 349,736

- Ulysses, 265,222

- Moby Dick, 206,052

But for the rest of us, the question lingers, shouldn’t any market-minded author, thinking about his/her audience understand the times and write accordingly? At least, throw in a few minnows into the shoal.

A final (happy) thought

There is an upside to all this. KDP authors are always advised that the Amazon algorithm favours the series – same characters and locations, but different stories. Think Harry Potter, of course, but also Ian Rankin’s Rebus series and Terry Pratchett’s Discworld.

So those who feel constrained by a short word count should think more strategically. Build an empire over time, each book in a series providing a different piece of the mosaic until the full epic masterpiece is revealed 20 books later.

Squeeze it in the short term, stretch it out in the long.

And shift more units in between.

James Ellroy’s famous edit

There’s a famous story about the brilliant crime writer and stylist James Ellroy, so startingly different in his approach he even has his own adjective now – Ellrovian. His stories are elaborate, drawn from outlines almost as large as the book itself.

His plots are like a game of Jenga, one miscalculated yank and the whole edifice collapses.

And that’s how he came about his famous telegrammatic, staccato style (which you either love or hate).

This, from his Wikipedia profile –

“This signature style is not the result of a conscious experimentation but of chance and came about when he was asked by his editor to shorten a novel by more than 100 pages.

“Rather than removing any subplots, Ellroy abbreviated the novel by cutting every unnecessary word from every sentence, creating a unique style of prose. While each sentence on its own is simple, the cumulative effect is a dense, baroque style.”

Here’s the opening paragraph from the book he shortened – LA Confidential:

“An abandoned auto court in the San Berdoo foothills; Buzz Meeks checked in with $94,000, 18lbs of high-grade heroin, a 10-gauge pump, a .38 special, a .45 automatic and a switchblade he’d bought off a pachuco at the border – right before he spotted the car parked across the line: Mickey Cohen goons in an LAPD unmarked, Tijuana cops standing by to bootjack a piece of his goodies, dump his body in the San Ysidro River.”