The golden age of TV has a new star – real life. So why have documentaries become big news? And what does it mean for good old-fashioned fiction?

Truth is stranger than fiction – but truth isn’t much of a stranger any more. It’s everywhere – at least in the form of documentaries.

Last week Sky went all-in, launching a trio of non-fiction channels – Documentaries, History and Nature – which matched the commitment made by the streaming brands, especially Netflix, which love a doc.

So what’s with all this non-fiction? Has the golden age of TV drama surrendered its crown to a collection of misfits, eccentrics, sex offenders and sports stars?

We’ve put together 5 reasons why documentaries, non-fiction and true-life tales are all the rage. Plus we ask: what’s wrong with fiction?

1. There’s money in documentaries

Let’s start with brass tacks. It’s dull but true – money talks. Since the explosion of true-crime podcasts (which we cover in our book The Lockdown Survival Handbook), advertisers have begun to hunt around for other vehicles. Where the money goes, so the production values follow.

2. There’s something to see

Gone are the days when an authoritative voice intoned sombrely over black and white stills of dead soldiers. The age of video – from CCTV to ubiquitous phones – means there’s footage of just about everything that ever happened.

Even the interference and pixelated colour blocks add authenticity and voyeuristic thrill to the experience of seeing a murderer up close and personal as he denies his crime to the cops.

3. Nothing but the truth

The whole truth and nothing but the truth. Maybe not, of course. Critics of The Last Dance (including some participants) decried the sycophantic adulation of Michael Jordan, suggesting his team-mates were spineless and ineffective in the presence of the legend. And the latest blockbuster, Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich, features a story by one of his victims who claims she had been exploited for her eyewitness account.

The politics aside, though, truth itself is a nebulous commodity. It’s the age of social media where facts are a hostage to divisive identity politics, bought by the highest bidder or the loudest voice. Newspapers are shutting down. TV channels opt for partisanship over balance. Who knows what’s going on really?

It’s reassuring that – in greater numbers than ever – people are seeking out some firm foundation for their beliefs – even if their beliefs might centre on whether Carole Baskin put her first husband in the Kit-E-Kat. Questioning assumptions, testing theories, wanting to see evidence for oneself – this is how truth and vibrancy survives.

4. Documentaries have stolen fiction’s best weapons

Documentaries used to tell their story this way: from beginning, through the middle and on to the end – school textbook style. A doc on the Second World War would start around 1935, get exciting around 1942 and head towards a finish round about Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech.

Now documentaries are built around fictional familiars, such as the twist and the cliffhanger. It pays to have the right raw material to do this, but now documentary film-makers have a greater spiritual connection with Hollywood film-makers than they do journalists, historians and cultural commentators.

They slice and dice, they mess with the viewers’ heads, they keep back vital information (sacrilege for a journo) in order to leave you swooning at the Big Reveal or the Big Tease.

5. Real people, real judgments

People like people. People like to like people and they like to hate people too (probably more so). That’s just evolution. We wired to make societies – elevate the leaders and expel the trouble-makers. So even if the doc is about something obscure, the people are fascinating.

Co-operation is key to prosperous societies, say the scientists. It’s why we grew a big brain, say the evolutionists. It’s a difficult job keeping a complex society together and one of the keys to success is being able to make swift judgments as to a person’s worth.

That’s a two-million-year-old process that brings us to The Staircase, Making A Murderer, The Thin Blue Line and other true-crime docs.

Guilty or not guilty? It’s like catnip to an evolved brain – and why you can’t help but chew it over with your in-crowd.

Hats off to the pioneers who led the way

There are many who ploughed a lonely furrow before the big bucks arrive – think of Michael Moore and his gotcha exposes and Ken Burns with his way with archival footage. But we’re going to pick out two.

The first is probably Serial, the true-crime podcast that changed the game. The reason is this: podcasts are intimate and they’re immediate. Host Sarah Koenig took us into a shocking journey into injustice with a picaresque soundscape that married the fact-finding exploration of the court-room drama or the newspaper campaign with the forensic exploration of character, activism and issue that fuelled writers like Charles Dickens.

David Attenborough was always a polymathic pioneer and his championing of the natural world started out in wonder and culminated, in recent years, in urgency.

His is the voice of documentaries. Meanwhile, the autumn of his long career has seen the blossoming of so many astounding filming techniques, married to any number of photo-realistic screens that he has put us where we need to be: in the frontline in the battle against climate change.

5 documentaries you have to see

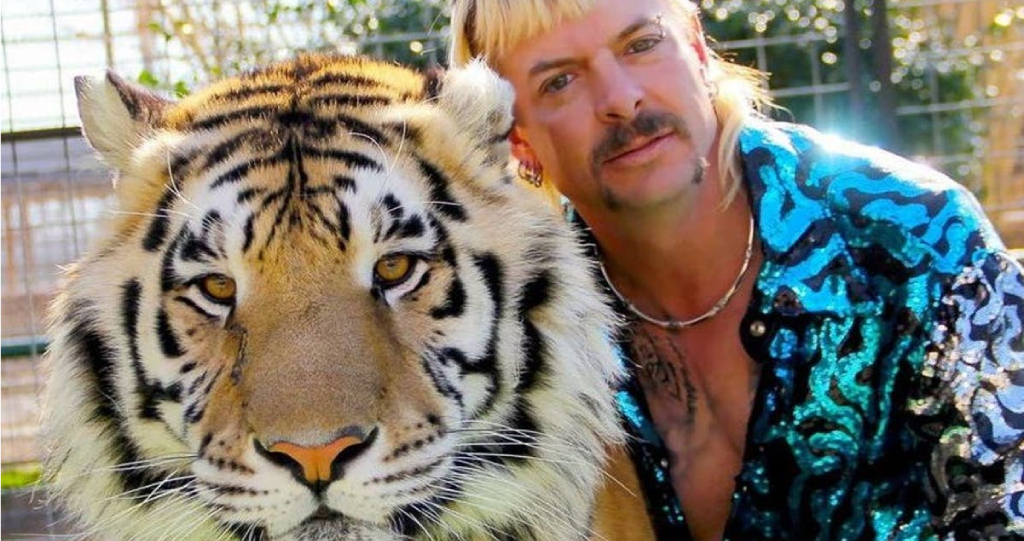

Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness

You come for the Big Cats, you stay for the wild ride. They’re making a film of this with Nicolas Cage – but what’s the point? It’s all here – death, guns, skulduggery, cults, cats – with the infuriating Joe Exotic centre stage, where he loves to be. If this wasn’t true, it’d be a Carl Hiaasen romp which you’d take with a pinch of salt.

Blue Planet

We’re citing this strand but anything that combines David Attenborough’s cosy gravitas with the long-suffering film crews who go to ridiculous lengths means we’re bound to see some of the most moving and sumptuous images ever likely to be broadcast. Ever.

The Last Dance

the mythologizing of sport and the marketing of sporting nostalgia meets its perfect match with the 1990s Chicago Bulls and a certain Michael Jordan. Sports docs are an up-and-coming sector and may have come of age in the coronavirus lockdown. There’s a sub-section geared to sport as a rite of passage. Check out Cheer, for example. Also, Last Chance U and The Dawn Wall.

Bowling for Columbine

Michael Moore has his critics, and his manipulative techniques are so obvious (and so effective) you can see him working the mechanics, but here he found a fitting subject for his rage – guns and their innocent victims. People who didn’t watch docs, watched this.

Blackfish

A heart-rending doc about Tilikum, a performing killer whale being captivity at SeaWorld. This is activism and film-making at its best, with SeaWorld cancelling its cruel breeding programme after it was shown.

What’s wrong with fiction?

Four possible answers:

People have become familiar with the “easy” solutions of fictions. Yes, the hero is going to appear to be dead about 15 minutes from the end, but there’s going to be a twist which means he’ll spring back to life. Compare a nail-biting sports final with an episode of CSI. Which possesses the true drama?

Fiction hasn’t successfully combined the weird and the mundane. We have the outlandish black comedies and the cosy domestic marital hiccups. But the genres stick safely in their lanes, so libraries and bookshops and streaming services know where to put them. Besides, who would dare try to sell a Donald Trump presidency as fiction, for example?

Time is short. People want quick fixes. Fiction demands the exploration of character and the steady growth of a plot that might, or might not, pay off. Documentaries plunge right in, their characters fully-formed and ready to perform, their stories already tested and refined in the market place by dint of copious media coverage.

Nothing. There’s nothing wrong with fiction. It’s fine. There’s bandwidth for everyone. Docs are having their moment, but people’s favourite moments still tend to be fictional.

How will fiction react?

Watch now as the pendulum swings the other way. Watch how fiction narratives start to steal the clothes of the documentary makers and use them to add authenticity to their wholly-made-up stories. Watch how the intrepid true-crime podcaster, and their like, becomes the 21st century’s gumshoe detective.

Expect to see a Fargo-style “Based on a true story” attached to a lot more novels.

Read more: How would our great writers cope in the lockdown?