Mutiny? Over a Bounty? Perhaps it’s time to return to the origin story of betrayal – and one of history’s biggest hatchet jobs on Captain W Bligh

The year is 1801, two decades after the Mutiny On The Bounty. Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson engages a tenacious Danish fleet to prevent Scandinavia succumbing to the influence of the French.

The storied Vice-Admiral penetrates the Danish blockade at Copenhagen, picking through the treacherous shoals along the harbour inlet. Already three of his 12-strong squadron have run aground and are out of action.

The hidden Danish batteries begin to unleash their firepower. In the melee and chaos, there is little room for manoeuvre, little time for considered action.

Nelson’s commanding officer, Admiral Hyde Parker, watches from afar, his flagship held back by the threat of shallow waters. He can make out only a little through the smoke. But what he does see is truly alarming.

Signals of distress from the three stricken vessels.

Parker, unsure of Nelson’s fate, runs up the “43” –Stop the battle!

Where Parker is cautious, Nelson is cavalier. He acknowledges the signal but famously ignores the command, keeping the “16” hoisted high for all to see – Continue the engagement.

I see no ships

“I only have one eye I have the right to be blind sometimes,” he tells his flag captain Thomas Foley aboard HMS Elephant. Holding his telescope to his blind eye, he says, “I really do not see the signal.”

However, another ship of his squadron, HMS Amazon, obeys Parker’s instruction and its captain, Edward Riou, withdraws.

Nelson’s support dwindles. The fate of the battle in the balance.

The captain of HMS Glatton is the only man who can now see both conflicting signals. He has to decide if he is willing to disobey his commanding officer, the Admiral, and throw in his lot with the adventurous Nelson. In doing so, the Glatton’s chief would seal the fate of the entire attacking English fleet.

He picks his fateful course of action. He flies Nelson’s signal and keeps the ships about him in the battle, earning praise from the great man himself for his contribution to the victory that follows.

And who was Glatton’s rebellious captain who defied his Admiral and stood by Nelson that day?

None other than 54-year-old William Bligh, arch-stickler, and a man who, ironically, became the poster boy for unyielding naval authority.

A Navy man betrayed by history

History has been cruel to the exceptional navigator and seaman who sailed with Captain James Cook and Admiral Nelson during a career that saw him rise to Vice-Admiral and Governor of New South Wales.

Bligh was, according to contemporary reports, thin-skinned and a strict disciplinarian (although not more so than any of his contemporaries). He was prone to dark moods and flashes of temper. But these were human frailties, not evidence of wickedness or moral corruption.

He was a flawed man, yes, and perhaps his greatest flaw was a lack of luck.

The fabled Mutiny On The Bounty was not even the only mutiny he experienced in his career. In 1797, he was one of the captains whose crews rebelled over “pay and involuntary service” during the Nore rebellions that infected the whole of the Navy.

And while Governor of New South Wales he clamped down on private trading ventures by soldiers and civil servants only to see those he thwarted rise up in the Rum Rebellion of 1808 when 400 soldiers marched on Government House, Sydney, to overthrow his regime.

With nowhere to go Bligh was effectively imprisoned on HMS Porpoise off the coast of Tasmania for two years.

The Mutiny on the Bounty

But it was none of these scrapes and adventures would put his name in the history books. It was his dealings on the Bounty that would make him notorious.

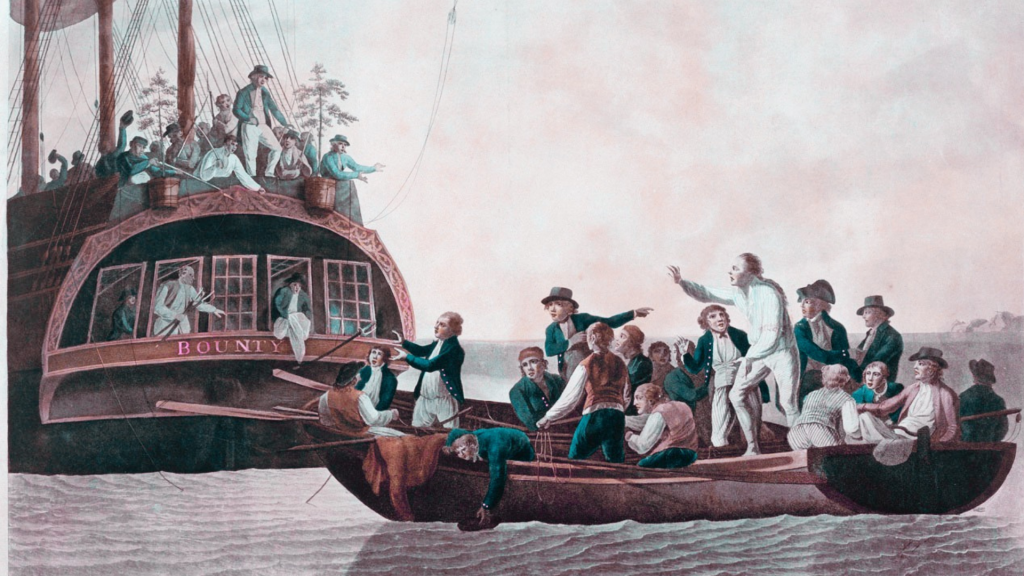

On April 28, 1789, after a bloodless coup, the then 35-year-old captain and 18 crewmen were deposited in a 7m cutter with four cutlasses, food and water, a quadrant and a compass and no charts and set adrift from the Bounty and into the treacherous South Pacific Ocean.

They were being sent to their deaths. None was expected to survive.

Yet, in this vessel Bligh showed his superlative seamanship and undertook a near-miraculous 3,618-mile voyage, reaching Timor in 47 days, losing only one crewmen, who was killed by hostile natives in a stopover at Tofua.

He and his men were able to return to Britain, where Bligh was feted as a hero, cleared by a court martial and able to resume his career.

So why did his crew mutiny?

- The curious case of a magic stone that caused ripples

- How prison inmates created a brilliant secret currency

It was the idyllic and soporific life on the Polynesian Islands that was the root cause of the unrest, according to historians. The inexperienced crew of the Bounty had been laid up in this paradise for five months, enjoying the sexual freedom and idleness that the islands offered. Better than anything they had ever known in England.

In contrast, life aboard the Bounty must have seemed like hell itself as it was for many Jack Tars in a world of shortages, discomfort, illness, warfare and strict discipline.

He kept his men alive

Bligh was not an unusually cruel leader. He ordered men flogged when the usual penalty was hanging, and the level of flogging was below the norm for the Royal Navy. He had kept his crew healthy when life at sea was a constant diet of deprivation and hazard, and he had kept their ship intact through the terrible storms of the Cape Horn.

Only a quarter of them opposed the captain – but for many the pull of the easy life of sexual liberation was sufficient to risk their lives and cast aside their grim naval existence.

The ringleader was Fletcher Christian, 24-year-old man, who had been until his troubles, Bligh’s friend and protege.

Mayflower – Birth of a Nation from Ravengate

Christian had started his naval career late, at the age of 17 and had first met William Bligh abroad the merchant ship Britannia three years before the mutiny in 1786. Despite Christian’s lower rank, Bligh had granted the Able Seaman the privileges of berthing in the officers’ quarters. Records show the boy’s conduct was generally satisfactory and he was promoted to the rank of Master’s Mate.

In 1787, Bligh asked Christian to serve aboard HM Armed Vessel Bounty for the two-year voyage to transport breadfruit from Tahiti to the West Indies. The Navy Board turned down a more senior rank for the young man, but Bligh appointed him a de facto acting lieutenant anyway.

But on the voyage, things turned ugly. Christian had become the target of Bligh’s irascible moods to the extent that the Master’s Mate thought about deserting long before mutiny crossed his mind. The breaking point was the theft of coconuts, for which Bligh blamed Christian – and the lure of the paradise isles.

A bayonet at his throat

In the early hours of the morning, 1,300 miles from Tahiti, Christian and his supporters took the upper deck. Three went to Bligh’s quarters, tied his hands and brought him to Christian. What a confrontation that must have been, the apprentice turned traitor.

Christian was waiting, with a bayonet in his hand and a weight around his neck so he could throw himself to his death if the mutiny failed.

“I have been in hell for weeks past. Captain Bligh has brought this on himself,” he told a friend.

In a letter to his wife Betsy in 1791, William Bligh wrote, “I demanded of Christian the case of such a violent act but he could only answer, ‘Not a word sir or you are dead.’ I dared him to the act and endeavoured to rally someone to a sense of their duty but to no effect.”

Of the 42 men onboard, apart from Bligh and Christian, 18 joined the mutiny, two were passive and 22 loyal to Bligh (four of whom stayed aboard the ship).

Bligh was deposited in that tiny cutter, lying dangerously low in the water and bearing enough rations for just a few days. There was nothing about them but hostile seas and fractious lands.

The family friend betrayed

Bligh pleaded with the friend he had tutored and supported to show mercy. “Mr Christian, I have a wife and four children in England, and you have danced my children on your knee.”

But Mr Christian was unmoved. And so began one of the greatest episodes of seamanship the Navy has chronicled, with Bligh never once forgetting his duties – maintaining his log and drawing up maps – while all the time bailing out the sea-swamped vessel.

“Our situation highly perilous, men half dead… Every person complained of violent pain in their bones,” Bligh wrote in his log.

But by the time the launch found Kupang on Timor, his careful management meant there were still 11 days of rations left.

After his return to England a year after the mutiny, Bligh was given command of HMS Providence and had left England in 1791 on a second breadfruit expedition.

His exulted place in history seemed assured.

Fate of the mutineers

Meanwhile, nine mutineers, including Fletcher Christian, the ringleader, sailed the Bounty to Pitcairn Island to settle. They burnt the ship to avoid detection.

Soon many would be dead, killed by each other or by locals. Some were caught by the British authorities and brought home on the HMS Pandora to be tried.

Christian would survive another handful of years on the Pitcairn Islands, dying at the age of 28, apparently in a conflict between mutineers and Tahitian men, although the manner of his death has remained a mystery. One fanciful theory placed him safely back in England. He left a wife Maimiti and three children. His descendants still bear the “Christian” name.

With Christian dead and gone, it was this rump of mutineers, now back in England, who would land the fatal blows on Captain William Bligh’s reputation. There was an orchestrated campaign to create a perception of Bligh as a cruel tyrant in an effort to win leniency and salvage Christian’s legacy. He was not without influential friends and supporters.

Fletcher Christian and the mutineers set Lieutenant William Bligh and 18 others adrift; 1790 painting by Robert Dodd

In 1792 the mutineers filled the court martial with tales of Bligh’s cruelty. Eventually, four were acquitted and six were found guilty and sentenced to death. Only three were actually executed – two received the king’s pardon; and another was discharged due to a procedural error.

The following year, Fletcher’s brother Edward Christian published his Appendix, a report on the proceedings that again put Fletcher in a favourable light and cast Bligh as a demon.

By the time Bligh returned to England, late in 1793, public opinion had turned against him completely. He would stay in the Navy, captaining a string of ships including the Glatton which played its pivotal role alongside Nelson at the Battle of Copenhagen.

How history turned on Bligh

But his luck deserted him again and, in 1805, Bligh was reprimanded for using bad language to his officers, which entrenched his reputation as unsympathetic authoritarian. A year later he was shipped off to New South Wales where the Rum Rebellion awaited.

He died, aged 63, in December 1817 in London and was buried in Lambeth.

Even then history would not leave him in peace.

The first published account of the mutiny was authored by Sir John Barrow in 1831. Barrow was a family friend of Peter Heywood, who was one of the mutineers brought back on the Pandora and only 15 at the time.

The boy had escaped hanging and he was one of the two who had received a Royal Pardon from King George III. This change of heart has been attributed to his family wealth and strong connections.

Sir John emphasised Bligh’s harsh regime in order to cast a favourable light on the young Heywood’s actions.

Heywood’s own stepdaughter Diana Belcher further exonerated him in 1870 and, according to historian Caroline Alexander, “cemented many falsehoods that had insinuated their way into the narrative”.

Hollywood didn’t help

Hollywood has helped with film versions painting the story in black and white – there was the 1935 Clark Gable vehicle that fixed Bligh in the public mind as the sadistic, plump and overbearing Charles Laughton character. And sharp-tongued Trevor Howard bullied the dashing Marlon Brando in 1962.

Clearly, Bligh was a man of duty, courage and skill. A navy man through and through, he was oblivious to his polarising effect and naively convinced that posterity would burnish his name.

He wrote, “My misfortune, I trust, will be properly considered by all the world. It was a circumstance I could not foresee. My conduct has been free of blame, and I showed everyone that I defied every villain.”

History would reach a different verdict.